For breakfast, I usually eat porridge. In fact, I’m quite sure everybody eats porridge at breakfast time. But only two hundred years back, savoury porridge flavoured with onions was all the rave, and for poor people it might have been supper rather than breakfast. Porridge was and still is, cheap and nutritious. Anyway, over breakfast, I was telling my friend today about the Robert Allen and Jane Humphries debate, which in a nutshell, is about the “high wage economy” (HWE). I told her about how the historian Robert Allen put the diets of women in the industrial revolution at around half that of men in his calculation of the HWE. My friend was offended at the simple fact that anybody could imagine women would be given half the portion sizes of men. But first, what is the HWE, and why is it important?

One reason Britain is said to have industrialized first is because of high wages, comparative to the rest of the world. Because of these “high wages”, there was a greater incentive for innovation of capital and the use of cheaper fuel – think spinning jenny, the mule etc. Allen’s (British industrial rev. p.38 /2009) methodology uses consumption baskets, where an idealized “bundle of goods”, such as oats, flour etc. are put in on a yearly basis. Imagine you are looking at the calorific content on the back of your cereal packet, and then multiplying your portion by 365 for a yearly amount. Your cereal would be one part of the basket. Dinner may be another. Robert Allen then came out with a figure (based on others too) from a which a family could survive, around 1,891 calories per day, and more for a “respectable family”. However, for a family with a husband, wife and say two or more children (likely more) the husband’s amount is given as equal to the wife and the children, giving the wife a seriously small nutritional amount. People were small back then, but were they always starving, even when working hard jobs?

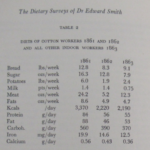

Jane Humphries in a paper aptly titled “the lure of aggregates and the pitfalls of the patriarchal perspective…” (2013) finds the level of consumption stated above rather low for women and children. Looking at the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) of the United Nations, Jane Humphries finds the amount of Human energy requirements for men to be 2,650-2,950 calories and women 2,250-2,500 calories per day, at a height of around 1.7 meters. Now the FAO is a modern measure, but the closest thing to a requirement comes from Dr Edward Smith who proposed “4,300 grains of carbon 200 grains of nitrogen daily”, or about 2,800 kcalories and 81 grams of protein. He found most indoor workers did not meet this standard, but outdoor workers may have exceeded it. By his measure, Humphries’ calculations appear to be more precise. Anyway, I digress, the point is that Robert Allen seriously miscalculates the amount of food women may need to eat compared to men – there’s lots online about this debate if you are interested.

Please sir may I have some more …

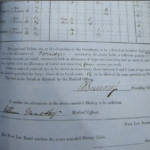

So on this point, something I came across in the British library is the dietary patterns of the inmates of the workhouses, in 1866. A point to note – this at least half a century after the “HWE” debate took place, the time period of which the above two historians wrote about. The picture shows us the diets of men women, and children, in a workhouse. Workhouses were not dissimilar to prison labour – tasks were menial, diets as we will see were terrible… Workhouses were occupied with orphans, paupers, the mentally unwell and destitute sex workers. I’m not sure there’s anything positive written about workhouses….

The image below shows the dietary “rations”, or the amount given to the inmates of the workhouse. Many more examples do exist thanks to Dr. Edward Smith, who conducted a nationwide survey of households in 1866. For breakfast, women get only half the amount of porridge compared to men every day for. For dinner women are given 1⁄4 the amount of men. Perhaps we should be happy that both men and women get the same amount of potatoes (16 ounces?) And porridge again for dinner… likely savoury onion porridge.

A final point: the real kicker… women were given the same amount as those aged 9 to 16! So to go back to the FAO requirements, where women need around 90 percent of calories of those of men, we can see that women were most likely starving, not to mention I imagine, fed up of porridge. We can see the historical standard of discrimination and oppression against women in the workhouse diets, not to mention, breastfeeding women who would have needed more calories. This may be only one workhouse, a further investigation would tell us more, but a brief summary of the works of Dr. Edward Smith show that starvation was fairly common up and down the country. Vegetables were in short supply and meat was eaten very rarely by the poor – as we can see the roast beef on Sunday and boiled meat on Tuesday and Friday. One can only hope that modern prisons offer better food, and equal food for men and women.

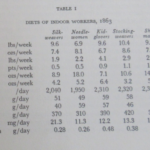

So to go back to the HWE debate, although this is at the end of the period, it would appear as though Allen’s baskets are more accurate for those in the workhouse. Not that this has any implications on the HWE debate. For the end of the HWE the following table on textile workers may in fact be more relevant. In short, the “indoor” workers, those in factories who weren’t working in their own homes were the worst off. Compared to the workhouse, they seem to be better off. Cotton workers in the North of England were comparatively, the best off. It would be very interesting to see how diets in the North vs South of England compare today.

Figures 1 and 2: Dietary for the inmates of the workhouse, National Archives, MH 12/9251

Figures 3 and 4: Dietary surveys of Dr Edward Smith 1862-3. Barker T.C.